|

How to Get a Curry in Victorian London

If you like curry, you have more in common with the Victorians than you might think. Their love of Indian dishes began with the officers and officials of the East India Company. These men enjoyed spicy meals in India, and still wanted to eat their favourites when they returned to Britain. Queen Victoria helped to further popularise the craze for all things Indian, regularly enjoying curries cooked by her own Indian chefs. This short guide will take you to the cigar-filled gentlemen's clubs and the elegant, high-class hotel restaurants serving curries made by Indian chefs; the noisy, aromatic warehouses where Indian entrepreneurs stored their imported spices; the sell-out audiences watching demonstrations of curry-making by experts in Indian cooking; and the cookery schools where domestic cooks employed in middle-class homes learned how to make curry. You'll also learn how curry powder made Indian-style meals more affordable (and less authentic), and why it could be a health risk. Curry in Victorian London was not available to everyone; it very much depended on your social class, gender and wealth. Spices were too expensive for the working classes, and only middle- and upper-class men were welcome in gentlemen's clubs and hotel restaurants (it was not socially acceptable for women to dine out without a male escort until the 1880s). But the British love affair with curry is firmly rooted in the Victorian period. The paperback edition of the guide runs to 65 pages, and costs £5.99. The Kindle edition is only £1.99 |

Agnes Marshall

Trailblazer, innovator, entrepreneur. Agnes Marshall was as famous in her day as Mrs Beeton, but she has largely been forgotten. Now David Smith has re-examined her achievements and contribution to the culinary world.  Starting as a scullery maid and later a cook, Mrs A. B. Marshall opened a renowned cookery school with her husband, Alfred. Agnes was endorsed by royalty; wrote four best-selling cookery books; invented improvements to ice cream-making machinery; established a weekly newspaper, The Table; and undertook popular lecture tours. |

art of curry making

Over the years, I have written many articles about the British love affair with curry. A while ago, I was invited to write an essay on the subject by the Canadian journal Victorian Review.  picture from Wikimedia Commons I was honoured to accept the invitation, and my essay was published last year by John Hopkins University Press in the latest edition of the journal. It is an academic journal and not generally available to the public, but the publishing agreement allows me to feature my essay here on The Curry House website. The title of the essay is "The Sublime Art of Curry Making" which is a quote from Culinary Jottings for Madras, by Colonel Arthur Kenney-Herbert ("Wyvern") who is the subject of my book The Cooking Colonel of Madras. |

|

the cookbook

Quick Meals from The Curry House contains over 50 recipes for making Indian restaurant-style meals at home. Most of the recipes can be made from scratch in under one hour.

The book has collections of recipes for House Specials, Curry House Favourites, Tandoori-style Dishes, Vegetable Bhajis, Rice, Breads and Relishes. The recipes make dishes that bridge the gap between restaurant meals and supermarket ready-meals. |

food history

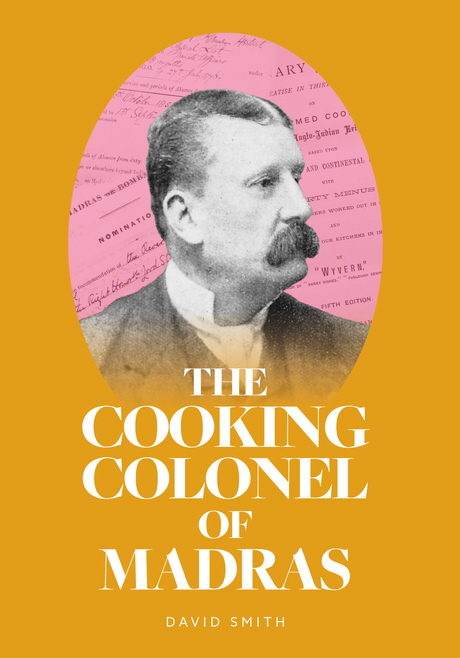

My book on the life and times of Colonel Arthur Kenney-Herbert: The Cooking Colonel of Madras.

Arthur Kenney-Herbert was a cavalry officer who served in India during the British Raj. Using the pen name "Wyvern", he wrote Culinary Jottings for Madras in which he gives instructions to British memsahibs on how to give refined dinners, manage their servants and make Anglo-Indian curries. His book was a great success, and made Wyvern famous in colonial India. When he retired to England at the rank of colonel, Wyvern built on his reputation as a culinary authority. He founded a cookery school, gave cooking demonstrations, and wrote books and articles for prestigious magazines. |